BY STEVE KRAH

http://www.IndianaRBI.com

Doug Wellenreiter has been swinging a fungo and dishing out baseball knowledge for a long time.

The 2019 season marks his 40th as a coach — five as an assistant at Goshen College after 35 in Illinois at the junior high, high school and professional level.

Since arriving on Hoosier soil, he’s also taken to coaching for the Michiana Scrappers travel organization in the summer.

What does he believe in as a coach?

“Hopefully my kids learn the game and it’s a lifelong value to them,” says Wellenreiter. “The values that you teach are not just baseball. You teach them things in baseball that will help them for the rest of their life — whether it’s discipline, being on-time or never say quit. You hope you have a lasting effect on kids down the road.

“I can’t tell you how many games I’ve won or lost (he actually 625 and went to the round of 16 in the Illinois High School Association tournament six times in 27 seasons at Momence High School). It really doesn’t matter.

“The only important thing is the next one. You don’t take the games with you. You take the people with you. That’s why (baseball’s) the best fraternity to be a part of.”

That fraternity may not have a secret handshake, but it’s given Wellenreiter plenty of memories and perspective.

“Lifelong stuff is what you take with you,” says Wellenreiter, who was pitching coach for a few summers with the independent professional Cook County Cheetahs. “I sometimes had a junior high game in the morning and a minor league game at night. I’m probably the only guy in America who coached junior high and minor league at the same time. Sometimes the junior high game was better.”

What’s the difference between junior high, high school, college and pro?

“In the big picture, the fundamentals of the game is the same,” says Wellenreiter. “It just happens at a faster rate at each level. At the pro level, it happens at 88 to 93 mph. At (the college) level, it happens in the low to mid 80’s. At the high school level, it happens in the 70’s.”

Wellenreiter sees freshmen working to make that adjustment when they arrive at Goshen.

“They may have seen a kid who threw 85 occasionally in high school,” says Wellenreiter. “Now, you’re going to see somebody like that almost everyday at our level. Everybody runs much better at this level. Everybody’s got a better arm.”

Before retiring in 2014 and moving to Goshen to be closer to be closer to one of his daughters and his grandchildren, Wellenreiter was a biology teacher and driver’s education instruction in Illinois.

“I never had any intentions of being a bio teacher when I went to Millikin (University) in Decatur,” says Wellenreiter. “They had the foresight into what the future was going to hold in the education field. You take so much science when you go into P.E. They said, you’re crazy if you don’t take the extra classes so you’re certified to teach science. Make yourself as marketable as you can. That’s all I’ve ever taught — biology.”

With that know-how, it has given the coach a different outlook on training.

“I know how cells work,” says Wellenreiter. “I know what origin of insertion means and the difference between induction and abbuction.”

At Goshen, Wellenreiter works on a staff headed by Alex Childers with Justin Grubbs as pitching coach.

“Alex gives me a lot of freedom,” says Wellenreiter, who knew Childress when he was a student and baseball player at Olivet Nazarene University in Bourbonnais, Ill., and Wellenreiter was an assistant men’s basketball coach for the Tigers (He was also a long-time basketball assistant at Momence) and later a part-time ONU baseball assistant.

Wellenreiter helps with scheduling (he has spent plenty of phone time already this season with postponements and cancellations), travel and, sometimes, ordering equipment. He assists in recruiting, especially in Illinois where he knows all the schools and coaches.

On the field, his duties vary with the day. While Grubbs is working with the pitchers, Wellenreiter and Childress mix it up with the positional players. He throws about 400 batting practice pitches a day and coaches first base for the Maple Leafs.

“When you’re at a small college, you have to be a jack of all trades to get things done. You don’t have a huge coaching staff. I’m part-time, but I’m like part-time/full-time.”

Wellenreiter makes up scouting reports before every game. He keeps a chart on every hitter and what they’ve done against each GC pitcher.

“I do it by hand,” says Wellenreiter. “chart where they hit the ball and plot whether it was pull, oppo or straight.

“The most important pitch is Strike 1. I chart that.”

Wellenreiter recalls a batter from Taylor University who swing at the first pitch just three times in 48 at-bats against Goshen.

“Gee, this isn’t rocket science,” says Wellenreiter. “If the guy isn’t going to swing at the first pitch, what are we putting down (as a signal)? Let’s not be fine. Let’s get Strike 1. Now he’s in the hole 0-1 and you’ve got the advantage.

“Sometimes, you can’t over-think it as pitchers. You’ve got to pitch your game and use your stuff. If the guy’s not catching up to your fastball, go with that. Don’t speed his bat up.”

Goshen coaches will sometimes call pitches from the dugout, but generally lets their catches call the game.

Wellenreiter says charts and tendencies sometimes backfire.

“I remember for one player, the chart said he had pulled the ball to the right side in all eight at-bats,” says Wellenreiter. “So he hits the ball to the left of the second base bag.

“That’s baseball.”

Wellenreiter learned baseball from Illinois High School Baseball Coaches Association Hall of Famer Jim Scott at University High School in Normal, Ill.

“That’s where I learned my stuff,” says Wellenreiter, a 1975 U-High graduate. “(Coach Scott) gave me a chance. I played on the varsity when I was a sophomore.”

Wellenreiter has added to his coaching repertoire as his career has gone along.

“You steal from here. You steal from there,” says Wellenreiter. “You hear something you like and you add it in.”

Smallish in high school, Wellenreiter ran cross country in the fall and played baseball for Pioneers in the spring. He played fastpitch softball for years after college.

“I miss playing,” says Wellenreiter. “ I had a knee replaced four years ago. I hobble around now.”

While coaching in the Frontier League with the Cheetahs (now known as the Windy City Thunderbolts), Wellenreiter got to work alongside former big leaguers Ron LeFlore, Milt Pappas and Carlos May.

One of Wellenreiter’s pitchers made it — Australian right-hander Chris Oxspring — to the majors.

Cook County manager LeFlore was infamous for running his pitchers hard.

“They had to run 16 poles (foul pole to foul pole) everyday,” says Wellenreiter. “Ox couldn’t do them all. We had to DL him because he was too sore and couldn’t keep up with conditioning.”

After spending 2000 with the Cheetahs, Oxspring was picked up by affiliated ball and played for the Fort Wayne Wizards in 2001 and made five appearances for the 2005 San Diego Padres.

Wellenreiter drove up to Milwaukee and spoke Oxspring after his MLB debut.

The pitcher called to his former coach and they met in the visitor’s dugout before the game.

“Hey, Coach Doug,” Oxspring said to Wellenreiter. “Remember those poles? I can do them now.”

Wellenreiter notes that Oxspring made more money in his 34 days with the Padres than he did his entire minor league career.

“That’s why guys fight to get up there,” says Wellenreiter of the baseball pay scale and pension plan.

While coaching the Momence Redskins, Wellenreiter got a close look at future major league right-hander Tanner Roark, who pitched for nearby Wilmington High School.

“I had him at 94 on my radar gun,” says Wellenreiter of Roark, who helped his school win Class A state titles in 2003 and 2005, the latter squad going 41-1. “He’s probably the best I’ve had to go against.”

Wellenreiter notes the differences between high school baseball in Indiana and Illinois and cites the higher number of games they play in the Land of Lincoln.

Illinois allows 35 regular-season games and teams are guaranteed at least one game in the regional (equivalent to the sectional in Indiana). In 2019, the Illinois state finals are May 31-June 1 for 1A and 2A and June 7-8 for 3A and 4A. Regionals begin in the middle of May.

The maximum number of season baseball games in which for any team or student may participate, excluding the IHSAA Tournament Series shall be 28 and no tournament 26 and one tournament.

When eliminated from the tournament, most Illinois teams will let their seniors go and launch right into summer ball, playing 40 to 45 games through early July. The high school head coach usually coaches the team.

“Any kid worth his salt is playing another 25 games in the fall,” says Wellenreiter. “That’s 90 to 100 games a year. The difference in experience adds up. Illinois kids are seeing more stuff.”

Coaching with the Scrappers, Wellenreiter’s teams have never played more than 28 contests.

Junior high baseball is a fall sport in Illinois and has a state tournament modeled after the high school event. The season begins a few weeks before the start of school.

Wellenreiter coached junior high baseball for more than two decades and guided many of the same player from Grades 6 through 12.

There are pockets of junior high baseball around Indiana.

At a small school like Momence (enrollment around 325), coaches had a share athletes. What Wellenreiter saw is that athletes would pick the “glory weekend” if there was a choice between two or more sports.

“One thing I don’t miss about high school is fighting for the kids’ time,” says Wellenreiter. “I never asked my baseball players to do something during the basketball season.”

At Goshen, Wellenreiter can focus on baseball and his family. Doug and wife Kelly have Brooke, her husband and children living in New Paris, Ind., with Bria and her husband out of state.

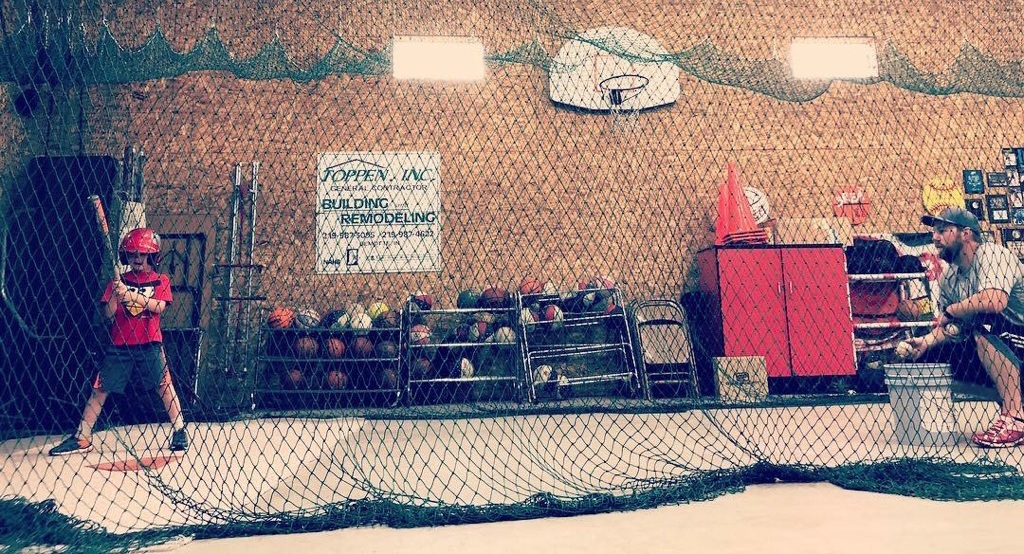

Doug Wellenreiter is in his fifth season as an assistant baseball coach at Goshen (Ind.) College. It’s the 40th year in coaching for the Illinois native. (Steve Krah Photo)